Onanist Cortnee Brush

Cortnee Brush doesn’t know what she is doing.

Exhibition Information

Artist: Cortnee Brush

Exhibition: Onanist

Media: Performance Art

Gallery: Long Beach State University, School of Art, Merlino Gallery

Website: na

Instagram:

Doubt

Commercial Art is often dominated by talented artists with strong, clear visions. Their confidence and clarity are part of what they offer clients. I’m not sure Fine Art can be that way. If one’s work is to be a genuine investigation, it may require doubt.

Doubt comes in many forms. Sometimes it is the methodical exploration of possibilities. Other times it can be a debilitating lack of confidence. In any of its many forms, I believe that doubt is at the heart of much of the most compelling work. I’ll take the insecure genius of an Andy Warhol asking everyone, what should I do next? over the machismated confidence of Richard Serra flinging hot lead against a wall.

In developing Onanist, Cortnee Brush started from a place of doubt. Doubt about her art practice. Doubt about object production. Doubt about not making objects. Doubt about Performance Art. Doubt about Documenting Art. Doubt about whether all art is masturbation.

Onanist

Onanist – a person who practices masturbation

— vocabulary.comOnanism – “masturbation,” also “coitus interruptus,” 1727, from Onan, son of Judah (Gen. xxxviii:9), who spilled his seed on the ground rather than impregnate his dead brother’s wife: “And Onan knew that the seed should not be his; and it came to pass, when he went in unto his brother’s wife, that he spilled it on the ground, lest that he should give seed to his brother.” The moral of this verse was redirected by those who sought to suppress masturbation.

— dictionary.com

Brush began the investigation that led to Onanist with doubt about her own art practice. Or perhaps the value of all art practice. Is it art if there isn’t some tangible product? What if it is only experience? Is that art? Or masturbation?

Performance

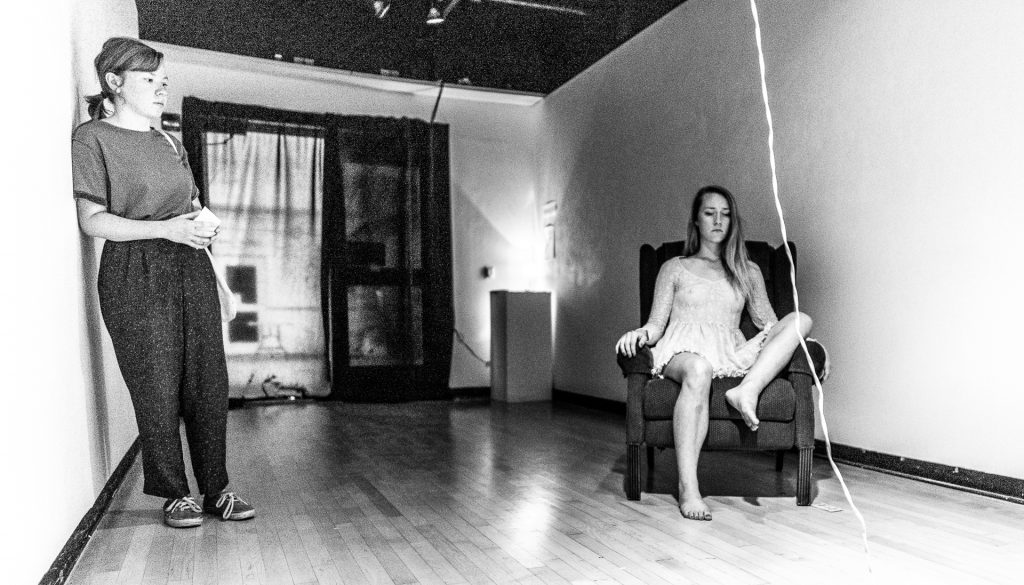

In an early version of this piece, Brush saw herself creating a figure to sit in the chair. Over time she decided the figure needed to be her own body.

Onanist is a durational work of about 40 minutes. As the work began I wondered why she scheduled performances at 12:30, 2:30, 5:30? Why wasn’t it simply a day-long performance of her in the gallery space? By the time the performance was over it was clear that this was not a scenario audience members could drop in and out of. If you’re only there for 5 or 10 minutes, nothing much happens. If you’re there for the complete 40-minute performance, you are witness to a sublime journey.

The work begins with Brush entering the gallery. Near the entrance, she removes her shoes and some excess clothing. In a lace dress, she sits in the large chair. After about 10 minutes the vibrator turns on. Apparently at some performances the vibrator dances around the floor, however at the performance I attended it didn’t move, instead simply vibrating in place. And adding its low hum to the music in the gallery and the various noises from outside the gallery. Once seated in the chair, Brush doesn’t appear to move for about 40 minutes. If you look closely, you can see that she is breathing, but not moving otherwise. Her eyes never closed, but across the 40 minutes, they seemed to ever so slowly grow narrower and narrower. Her body was relaxed and her facial expression was neutral. Her face seemed to take on a slightly greater intensity over time. Late in the work, several tears streamed down her cheek. In the stillness of this piece, these tears were powerful moments.

After vibrating for about half hour, the vibrator turned off. A few moments after it turned off, Brush picked up a condom from the floor, tore the package open, and took out the condom. She moved from the chair to the floor where she picked up the vibrator, took a condom off it, and put the new one on it. Placing the vibrator back on the floor, she got up and moved to the entrance. After putting on her shoes and extra clothing she left the gallery.

When I entered the gallery a few minutes before the performance began, I didn’t know how long it would run. 3 minutes? 90? During the time of the performance, I had no idea how much longer it might run. And then it was over. And suddenly the whole, amorphous journey took on so much definition and clarity. I felt that I had been witness to a powerful human experience. To a cathartic journey.

In his beautiful 2001 book Andy Warhol, Wayne Koestenbaum describes viewing a long, durational, Warhol film where “nothing much happens”. Koestenbaum wants to take notes on his pad, but he is afraid to take his eyes off the screen for fear of missing something. Onanist had this quality. During the performance, a number of people entered and exited the gallery, usually staying only for one or a few minutes. I wonder what their experience of this work was? It seems like “nothing much happens” in 5 minutes. Yet after 40 minutes, you have witnessed a powerful human experience. The sort of experience we rarely have the opportunity to witness.

A Non-Narrative Journey

I took a journey with a performance artist. In reading books, or watching films or plays, we also take journeys. The parameters of these are typically more defined. I watch the pages turn as I read the book. I know the film is two hours and I can see the plot points and act breaks. In Brush’s more amorphous experience I didn’t know the terrain. Yet with the performance’s end, the whole journey came into focus. Allusions to masturbation and sex and buzzing vibrators might bring ideas of frantic cadence to mind. But Brush’s performance was, at least formally, quite the opposite.

Where was she during this 40 minutes? In meditation? In memories? Was she imagining physical experiences? Relationships? Moments? The vibrator seemed to me like a candle or campfire. She was a part of its glow. But if it was the central flame, she was somewhere on the periphery. Somewhere in a very interior, deeply personal journey.

What was my role as audience? To watch, or experience, her journey? Or to focus on the vibrator flame and take my own journey. I did some of both. At times I closed my eyes and focused on sounds. Other times I focused on the palpable, if nearly frozen, presence of Brush. My meditation was far less deep than Brush’s. I didn’t go where she went, but I watched her go there. It didn’t feel voyeuristic in the experiencing, but perhaps it was. It was a performance of great vulnerability and generosity. I wonder how many others had the complete experience of her performance, and not just a few minutes peek at a space where “nothing much happens?”

Merlino Installation

I love the Long Beach State University, School of Art, Merlino Gallery because of it’s small size and extreme aspect ratio. I’ve always thought of it as the site-specific gallery. Yet in conversation with Brush after the performance, we both wondered if, in this case, the gallery and the particular staging did not help her audience. What about a not-so-narrow gallery, like the LBSU Dutzi gallery? There she might arrange pillows in a perimeter of shadows which could invite more viewers to see the complete performance. With the Merlino installation, many viewers seemed inhibited. Seemed afraid to cross one of several liminal zones.

Some visitors simply didn’t get past poking their head through the black drape. Others did enter but stayed in the entrance area with the lamp and comment book. For those that ventured further, the chair seemed to mark a sort of proscenium space beyond which the audience presumed it wasn’t supposed to go. In a more round installation with floor pillows, gallery visitors would have a much clearer invitation to enter the space. I was fortunately too ignorant to sense the invisible line of the chair and so I viewed part of the performance from a far corner of the gallery. Seeing Brush more directly was powerful. It might be inserting more gaze into the space, and as an audience member you do feel more on-stage yourself, but it is also a rich experience.

The Grey Goo Problem

In the coming age of nanobots, self-replicating carbon structures that can make all sorts of wonders from simple replication instructions, one big concern is The Grey Goo Problem. In addition to doing whatever they do, it is essential that the nanobots contain a stop replicating instruction. Without such an instruction it is possible that the nanobots would transform all matter on earth without stop. Eventually all life on earth would be repurposed into creating an almost infinite ocean of nanobots. The surface of the earth being transformed from the diversity we know today, into an endless mass of nanobots. Of Grey Goo.

If you rewind 21 centuries, small, persecuted religions, like nanobots, encoded a reproduce! instruction. But unlike our hopefully regulated nanobot future, these religions did not contain a stop reproducing instruction.

A small, persecuted, literally underground (catacombs) religion needs a reproduce instruction to survive. “Wasting seed,” as in Onanism, is a sure path to extinction. It is understandable that an early religion would tie powerful biological urges to survival of the religious culture. And so, not wasting seed, not indulging in masturbation, coitus interruptus, birth control, homosexuality, abortion, became core instructions. 7.5 billion human beings later, religion, and other factors, have brought us the grey goo problem. But this grey goo problem is not made of nanobots, but of humans.

Today the species on top of the earthly life pyramid reproduces out of control. With no predators. With no self-regulation in response to ecological niche. With no stop reproducing instruction. Today it is not only acceptable to decouple pleasure from reproduction, it is essential for our survival. The onanistic imperative to not waste seed doesn’t work anymore. It needs to be turned off.

Documentation is Capitalism

At some point, nanobots need to stop reproducing. At some point, humans need to stop reproducing. What about Art? Do we have too much art? Do we need all the pieces tucked away in every artist’s studio? In every art gallery storage space? In every art museum vault? Do we need it all? Or should we let it go? Should we be Art Onanists?

At her Situation Room last year, Micol Hebron told me that she has documented none of the myriad performances and installations she has facilitated there. When I expressed surprise, she offered,

Documentation is Capitalism

This was a new thought for me! And I’m still grappling with it. As someone who loves documentation, I’ve never fully made my peace with Snapchat. I’ve never used the term, but perhaps a part of me thinks that Snapchatters are New Media Onanists.

Using Snapchat doesn’t decree that nothing be preserved. It only decrees that not everything need be preserved. In the many meanings of Onanism in Brush’s work, is one a call to make ephemeral work that can’t be made object? Pleasure and experience without reproduction? Ephemeral work that can’t be bought or sold? Is documenting the work as I’m doing right now subverting this intent? If so, can I take solace in only occupying a few bits on a web server and not killing any trees or taking up physical storage space?

Making objects, and documenting work, does play into the money and power of the art market. Ephemeral practices like Hebron’s Situation Room subvert this commodity-capitalism impulse in art. Brush’s Onanist is a work that can be documented, but like so much Performance Art, or Land Art, it cannot be truly experienced through documentation. Documentation is essential to the history of Performance Art, of Land Art, of Site-Specific Installation. Most of the work that comprises the corpus of these investigations is known more through documentation than through direct experience. Yet, as was clear at Brush’s performance, while documentation is essential to advance the discussion, it is not experiencing the work. It is not having the experience that the Onanist had in her moment.

One thought on “Onanist Cortnee Brush”